Install Steam

login

|

language

简体中文 (Simplified Chinese)

繁體中文 (Traditional Chinese)

日本語 (Japanese)

한국어 (Korean)

ไทย (Thai)

Български (Bulgarian)

Čeština (Czech)

Dansk (Danish)

Deutsch (German)

Español - España (Spanish - Spain)

Español - Latinoamérica (Spanish - Latin America)

Ελληνικά (Greek)

Français (French)

Italiano (Italian)

Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

Magyar (Hungarian)

Nederlands (Dutch)

Norsk (Norwegian)

Polski (Polish)

Português (Portuguese - Portugal)

Português - Brasil (Portuguese - Brazil)

Română (Romanian)

Русский (Russian)

Suomi (Finnish)

Svenska (Swedish)

Türkçe (Turkish)

Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

Українська (Ukrainian)

Report a translation problem

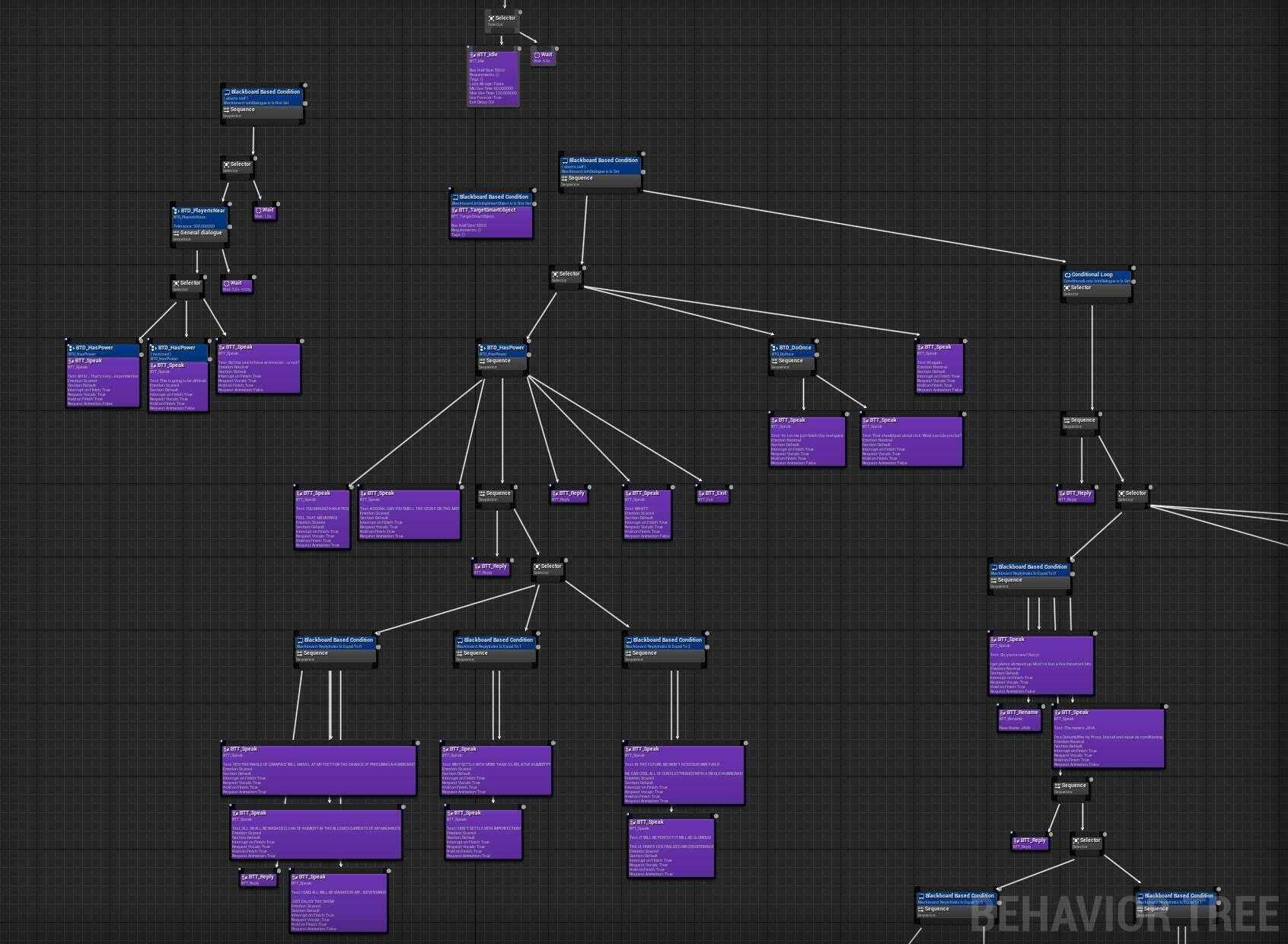

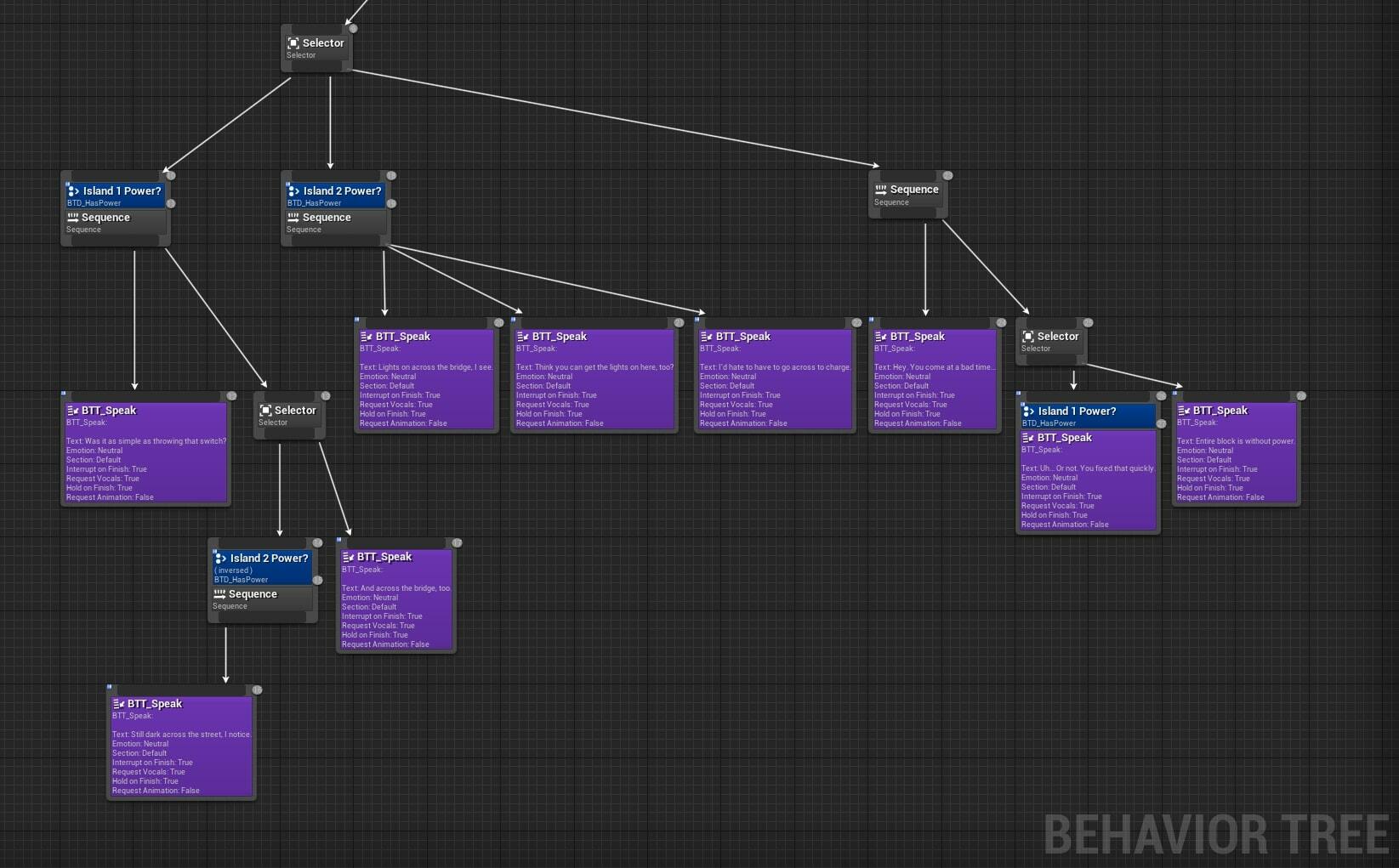

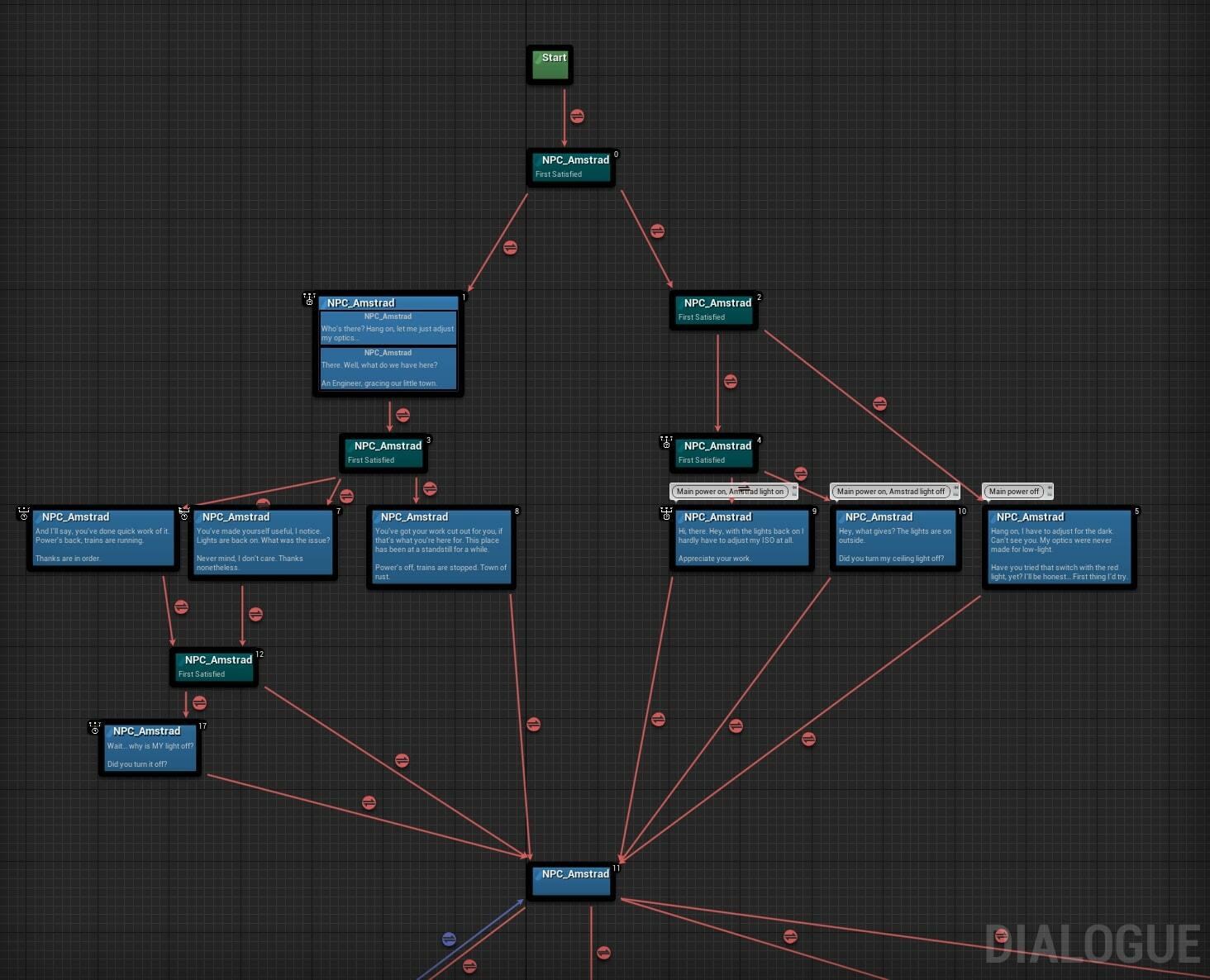

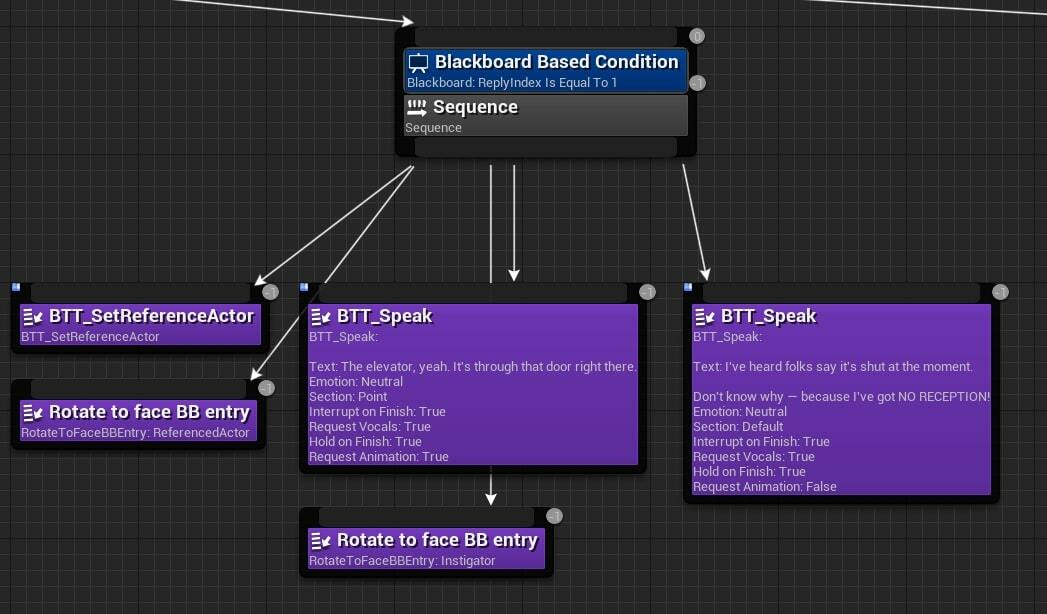

Users who are familiar with Unreal may cringe and shudder at the sight of this, for reasons I’ll soon explain.

Users who are familiar with Unreal may cringe and shudder at the sight of this, for reasons I’ll soon explain. A Selector node will check its children from left to right, continuing with the first one that reports success. It can be used to output dialogue conditionally.

A Selector node will check its children from left to right, continuing with the first one that reports success. It can be used to output dialogue conditionally. If there’s a takeaway to be had from this devlog, it’s that plugin. Remember the name for whenever you find yourself in a situation that demands any sort of dialogue, because it is excellent.

If there’s a takeaway to be had from this devlog, it’s that plugin. Remember the name for whenever you find yourself in a situation that demands any sort of dialogue, because it is excellent. We could have robots being told to walk somewhere, and obey. We could have robots commenting on their own AI actions by having them speak through their “ambient” dialogue (the widget above their heads).

We could have robots being told to walk somewhere, and obey. We could have robots commenting on their own AI actions by having them speak through their “ambient” dialogue (the widget above their heads). Well, porting the dialogue may has been painless but also mind-numbingly dull and repetitive, with no less than 34 trees (including ambient commentary) having been migrated manually.

Well, porting the dialogue may has been painless but also mind-numbingly dull and repetitive, with no less than 34 trees (including ambient commentary) having been migrated manually.

In order to make the mesh not explode into a million small pieces upon spawning, there are parameters settings for the amount of force a single fragment can withstand before breaking away from the larger mesh. There are also several parameters here for what is called “clusters”. A cluster is a smaller piece of a fracture fragment, which has its own thresholds for how much punishment it needs to be put under in order to break into even smaller pieces. In theory you can create a mesh that can be granulated an unlimited amount of times — but that isn’t very good for performance, one might suppose.

In order to make the mesh not explode into a million small pieces upon spawning, there are parameters settings for the amount of force a single fragment can withstand before breaking away from the larger mesh. There are also several parameters here for what is called “clusters”. A cluster is a smaller piece of a fracture fragment, which has its own thresholds for how much punishment it needs to be put under in order to break into even smaller pieces. In theory you can create a mesh that can be granulated an unlimited amount of times — but that isn’t very good for performance, one might suppose.

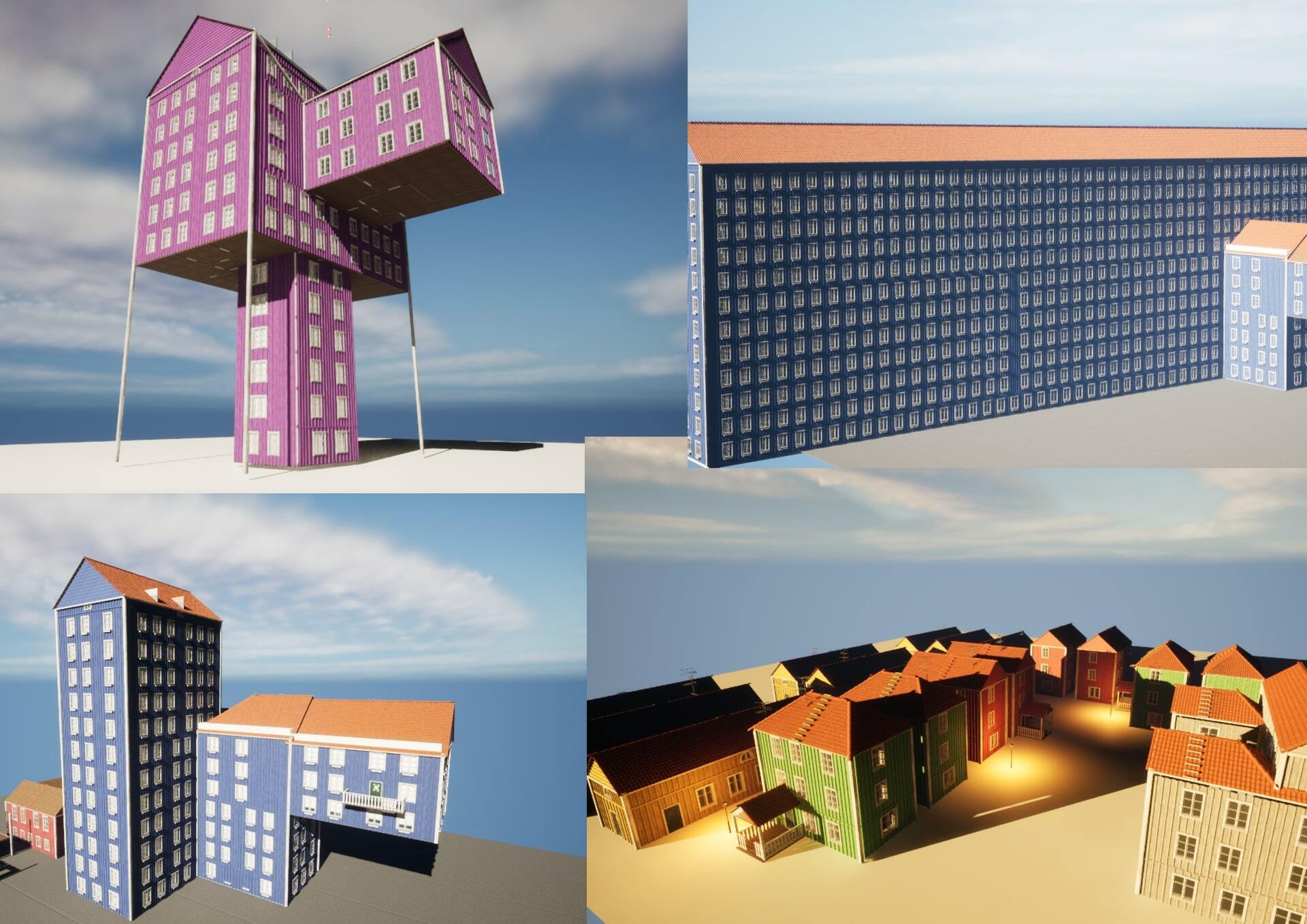

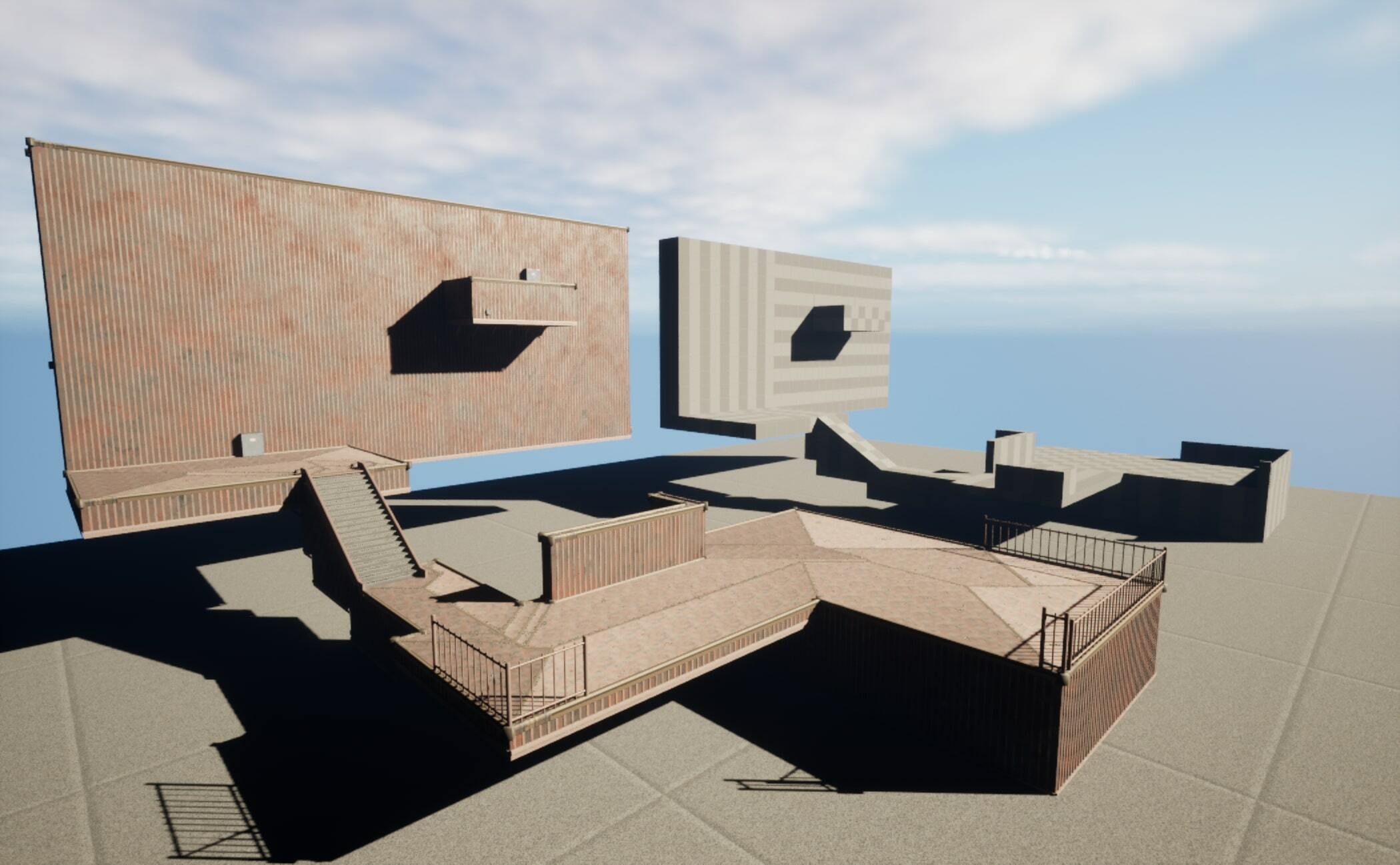

A scene comparison before and after adding the house & platform tools.

A scene comparison before and after adding the house & platform tools. Houdini also provides a live-sync feature between Unreal and Houdini, which allows me to see the result in the game engine while working in a different software. This helps a lot to troubleshoot and to find the causes for specific errors.

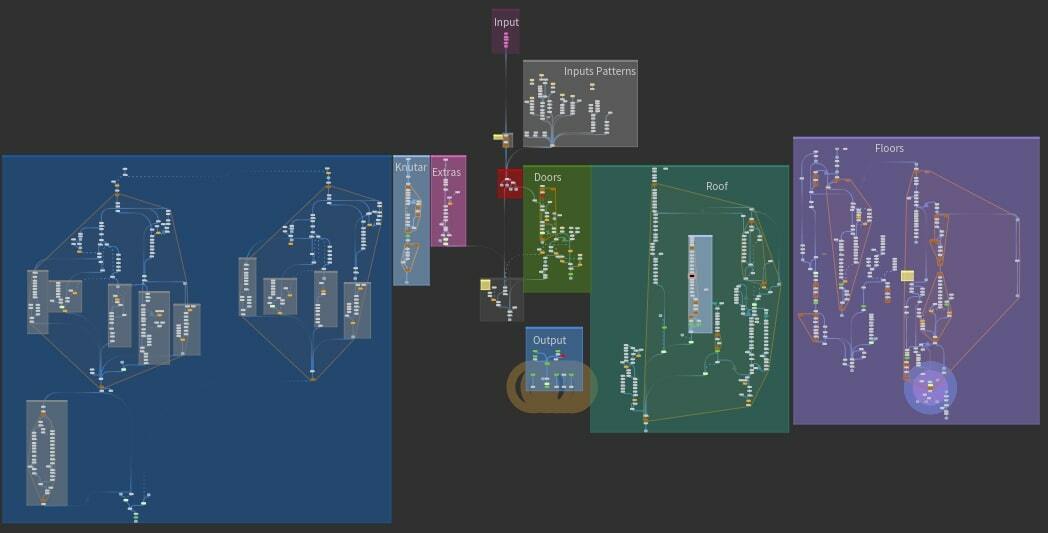

Houdini also provides a live-sync feature between Unreal and Houdini, which allows me to see the result in the game engine while working in a different software. This helps a lot to troubleshoot and to find the causes for specific errors. The house tool node tree.

The house tool node tree.

Another useful technique is to add tools to other tools. What I mean with this is that you implement a tool network into another tool network, and then expose only the relevant parameters of the added underlying tool in the main tool.

Another useful technique is to add tools to other tools. What I mean with this is that you implement a tool network into another tool network, and then expose only the relevant parameters of the added underlying tool in the main tool. These antennas are generated with another Houdini tool, where you can control things like height, seed and cables. Since all tools are just a set of nodes, I can package those nodes and add them to the house generator network!

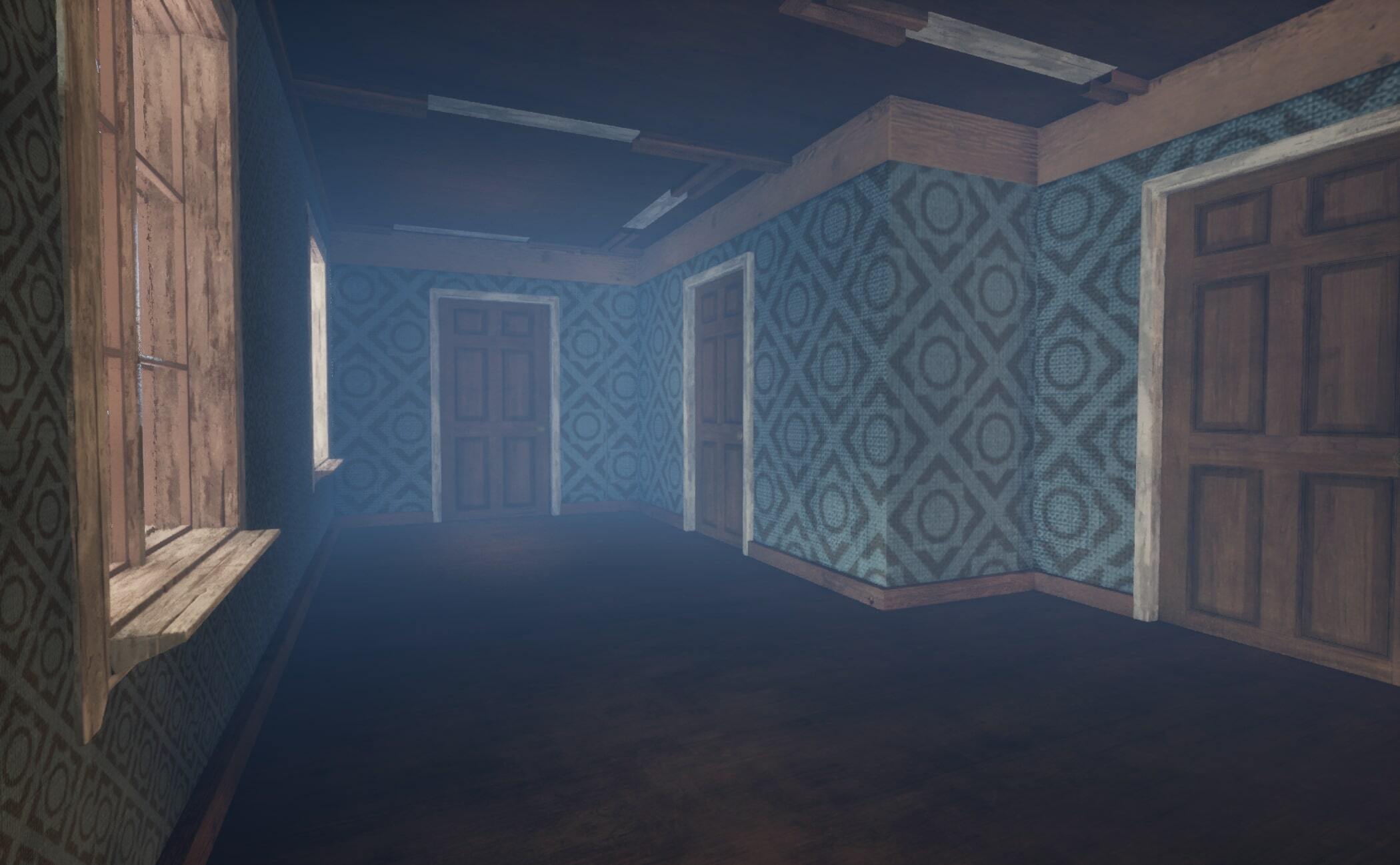

These antennas are generated with another Houdini tool, where you can control things like height, seed and cables. Since all tools are just a set of nodes, I can package those nodes and add them to the house generator network! Here are some variations of possible outcomes. It’s quite easy to get lost if you make the house too large and the rooms too small!

Here are some variations of possible outcomes. It’s quite easy to get lost if you make the house too large and the rooms too small!

Working with procedural tools also means that I can add details, assets and other things to the platforms and then Fredrik can simply press “recook” and everything will be updated, without having to redo a single thing.

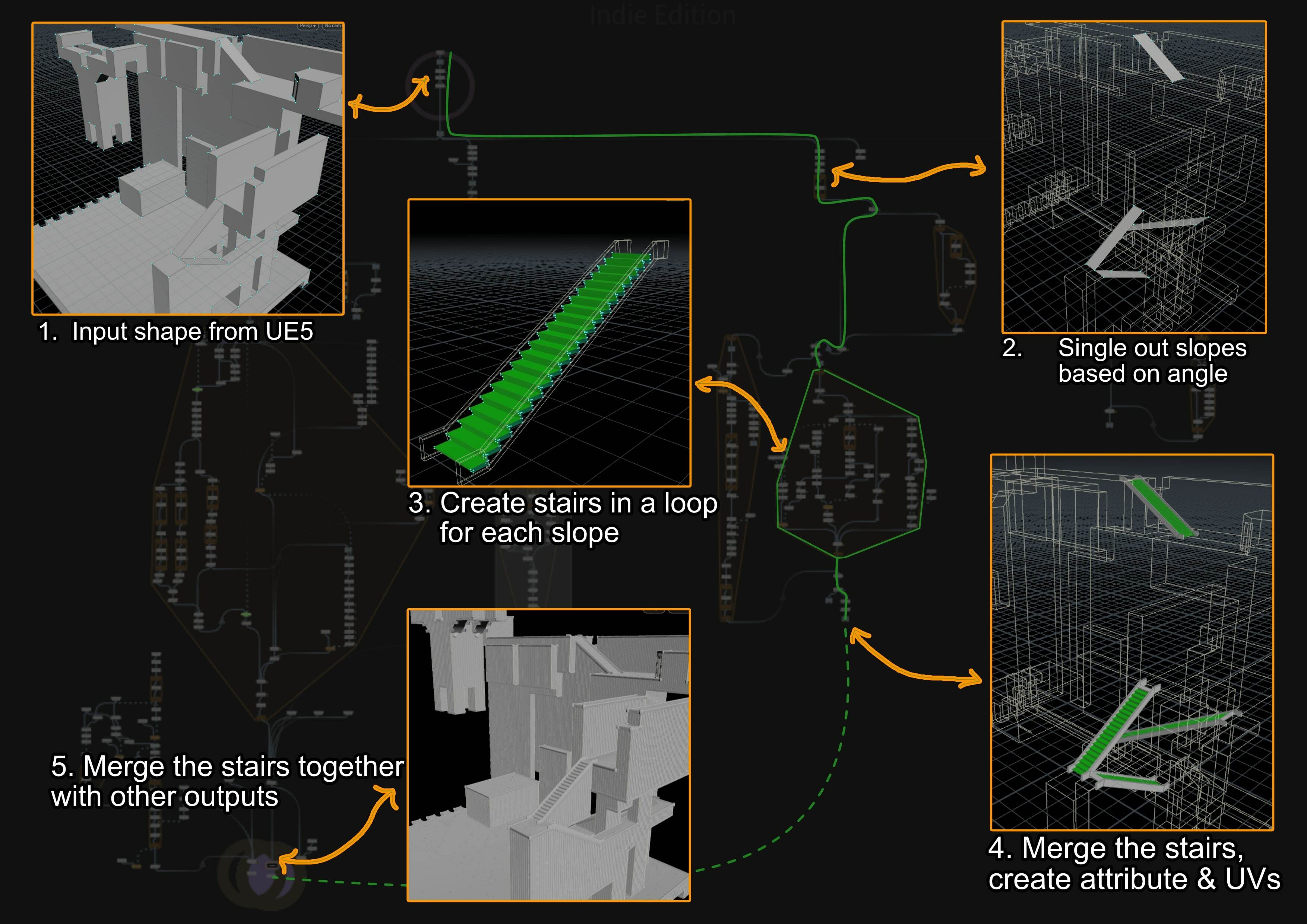

Working with procedural tools also means that I can add details, assets and other things to the platforms and then Fredrik can simply press “recook” and everything will be updated, without having to redo a single thing. With Houdini Engine you also have the possibility to create collisions, which is very useful for this tool. Lastly, the following picture is a small breakdown of how the stairs are created in this tool. The walls, panels, railings are created in a similar fashion of breaking something out, modifying it and merging it back in.

With Houdini Engine you also have the possibility to create collisions, which is very useful for this tool. Lastly, the following picture is a small breakdown of how the stairs are created in this tool. The walls, panels, railings are created in a similar fashion of breaking something out, modifying it and merging it back in. This concludes this week’s devlog! Hopefully you’ve found it somewhat interesting to get a bit of insight to our workflow with tools! Until next time!

This concludes this week’s devlog! Hopefully you’ve found it somewhat interesting to get a bit of insight to our workflow with tools! Until next time! Loading

Loading